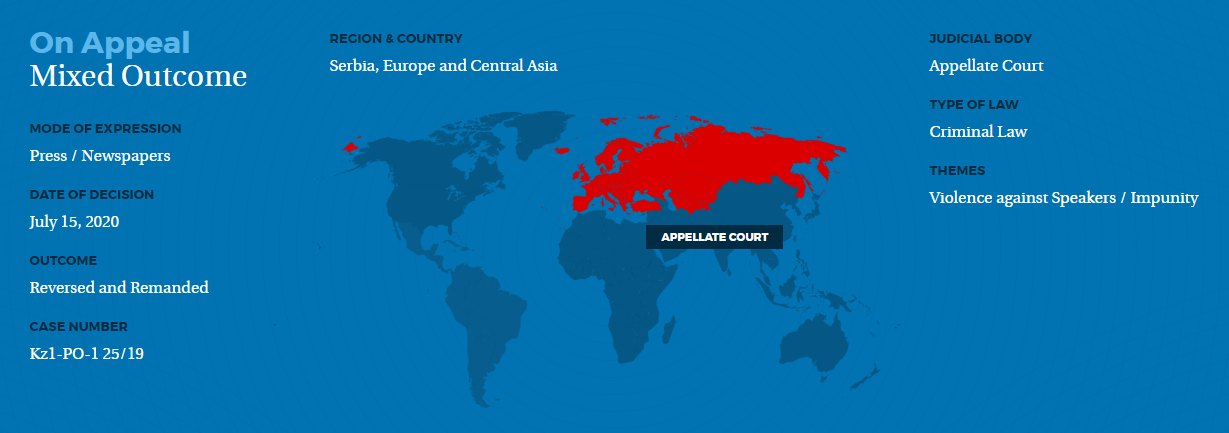

Source: Global Freedom of Expression, Columbia University

Facts

On April 11, 1999, shortly after returning from a trip to the U.S., journalist Slavko Curuvija was shot in the back 14 times in front of his house in Belgrade, Serbia. Publisher of the daily newspaper Telegraf and the magazine Evropljanin, Curuvija, was one of the most prominent and influential opponents of Slobodan Milosevic’s regime. It is widely believed that his anti-government speeches and writing lead to his murder.

In March 1998, while running a story about the conflict in Kosovo, Slavko Curuvija’s newspaper Dnevni Telegraf published a front-page photo of the massacre of the Kosovo-Albanian family Jashari – a topic that was unthinkable to discuss publicly at that time. Hence, Curuvija was summoned by the police to discuss the publication of the photo.

In October 1998, the Serbian government passed a draconian information law to curb critical reporting in anticipation of NATO’s military intervention in Kosovo. The law enabled authorities to identify media outlets allegedly undermining the State, along with other provisions which the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) stated were in contravention of numerous international conventions.

Soon after, pursuant to the new law, the editorial office of Dnevni Telegraf was sealed by the police, on the premise that the newspaper openly disputed government policies. In order to continue publishing, Curuvija registered the newspaper in neighboring Montenegro and moved his operations there, but the police were able to seize most of the copies destined for Serbia at the border, and only a small percentage ever made their way through.

In that period, under the auspices of the same Information Law, Dnevni Telegraf was the subject of two more lawsuits, and a private one, from then Serbian Deputy Prime Minister Milan Bojic.

Concurrently, in another challenge to the government, Curuvija’s magazine Evropljanin, featured Serbian strongman Slobodan Milosevic on the cover with the question “What’s next, Milosevic?” Inside was an article entitled “Letter to the President”, in which Curuvija accused the president of systematically degrading the church, judiciary, parliament and government. For this, the magazine was sued by the phantom organization “Patriotic Alliance of Belgrade” and convicted by a court of “undermining the constitutional order.” Curuvija had 24 hours to pay heavy fines related to his conviction, and after he was unable to pay, the police surrounded his house and began confiscating his property.

At the beginning of the NATO bombing campaign of Serbia, on March 24, 1999, war censorship became official, mandating all media to submit content for approval, and Curuvija ceased publishing both of his newspapers.

On April 6, 1999, during prime-time, the state TV broadcaster read an editorial which was to be published the next day by Politika Express, a daily aligned with the government. The editorial alleged that Slavko Curuvija bore some responsibility for the bombing of the country. It quoted Mira Markovic, wife of Slobodan Milosevic and president of her own political party in Serbia, as saying that ”the betrayal had reached its highest point” and that an owner of a Belgrade daily told her that he supported the United States in their desire to bomb Serbia and that the bombing would teach Serbs a lesson. The editorial revealed the identity of the media owner as Slavko Curuvija, further alleging that through his newspaper, Dnevni Telegraf, he did everything he could to explain to the “democratic West” and “misguided Serbs” how to course-correct since the future “belongs to the West.” The next day, the editorial was cited several times on different TV programs.

Four days after the editorial was published, Slavko Curuvija was assassinated. Branka Prpa, his partner at that time, was with him and she sustained a head injury after being knocked unconsciousness by a pistol. It is believed that she was the only eyewitness to the murder.

In 2001, after democratic changes in Serbia, there was hope that the new government would work towards resolving cases of murdered journalists, including Slavko Curuvija. However, in 2003 Prime Minister Zoran Djindjic, the driving force behind the changes, was assassinated and the investigations slowed considerably.

In 2014, the Public Prosecutor announced that it had testimony about the identities of Curuvija’s killers from Milorad Ulemek (AKA “Legija”), a former commander of the Special Police Forces, who was imprisoned for being implicated in the assassination of prime minister Djinjdjic.

In 2015, in front of the Special Court for Organized Crime in Belgrade, the Prosecution brought the case against four members of the State Security Service – Radomir Markovic, Ratko Romic, Milan Radonjic and Miroslav Kurak, charging them with organizing and implementing the killing of Slavko Curuvija. During the criminal trial, Ulemek’s above mentioned testimony was again presented which attested that Rade Markovic, at that time the head of the State Security Agency, tried to commission Ulemek to kill Curuvija, and later told him the identities of the perpetrators, as well as that Miroslav Kurak, a lower level operative, was the killer.

After four years of deliberations, on April 5, 2019, the court concluded that all four suspects were responsible for the murder of Slavko Curuvija, and sentenced them to between 30 and 40 years each in prison.

Both Prosecution and the Defendants appealed the decision.

On July 15, 2020, the Appellate Court (second instance) reversed and remanded the Special Court ruling, citing flaws. It is unclear at the time of this writing whether there will be a full retrial.

Decision Overview

Higher Court in Belgrade, the Special Court for Organized Crime (First Instance)

On April 5, 2019, the Higher Court in Belgrade, the Special Court for Organized Crime (First Instance), handed down the ruling in the murder trial of journalist Slavko Curuvija. Judge Snezana Jovanovic delivered the decision of the three-judge bench.

In the course of the trial, over 90 main hearings were held and the Court heard testimony from over 100 witnesses. All four Defendants pleaded not guilty.

The Court began by exploring potential motives for the crime. The Court established, based on the evidence presented, that Slavko Curuvija had been a person of interest to the secret service since 1994, and that since 1998 his phone conversations were monitored. [p. 74] The Court observed that in his public work Slavko Curuvija was a sharp critic of the politicians in power, that he spoke out against them publicly both domestically and abroad, which were some of the reasons that his newspapers were officially banned. [p. 79]; that his newspaper Dnevni Telegraf was “the key independent media” which represented “democratic opposition in the Serbian society,” and that at the time of his murder, Curuvija was one of the organizers of public debates titled “Staying Silent is Not Serbian Way.” [p. 81]

In particular, the Court found a statement by the journalist Dragan Kojadinovic to be credible. He explained that on October 20, 1988, the new Information Law was enacted, which was perceived by some members of the press to be a type of “Court Martial”, since it called for immediate adjudication of any offenses, any penalty to be paid within 24 hours, and all orders to be implemented within 48 hours, and that Slavko Curuvija was the first person convicted under the new law. [p. 79] The Court was of the opinion that such treatment was “undemocratic” and indicative of the fact that the “political regime which was holding the power in Serbia at that time” was running out of options, and that it was “ready for the most repressive measures.” [p. 80] The Court was also persuaded by the testimony of Slavko Curuvija’s daughter, Jelena Curuvija – Djurica who said that the only confrontation that her father had was with Mirjana Markovic, after he told Markovic that because of what they were doing, she and her husband Slobodan Milosevic would end up hanged on the main square. [p. 81]

The Court also found the testimony of Djordje Martic to be credible. He confirmed that he was the editor of the article “Curuvija welcomes bombs” which was written after he saw a text by Mirjana Markovic in which she said that she had a private conversation with Curuvija who told her that “Serbia has to be bombed” and that was the reason why he wrote the article. [p. 82]

The Court then turned to the evidence linking the Defendants to the crime. Specifically, detailed evidence was presented showing that Curuvija’s movements and phone conversations were carefully monitored by the State Security Service and that the Defendants were aware of that. In addition, the Prosecution presented data collected from the mobile phone towers showing the movement of the Defendants which placed Ratko Romic, Milan Radonjic and Miroslav Kurak in close proximity to Slavko Curuvija at the time of the killing. The Prosecution argued that the orders came from the highest echelons of the Serbian government, and the perpetrators acted in a manner of an organized criminal group with a mandate to kill.

Milorad Ulemek, in his witness testimony accepted by the Court, stated that in late March 1999, he met with Radomir Markovic who told him that “a certain person needs to be liquidated ” [P. 83], and asked him if he could do it.

During the trial, the Prosecution maintained that the shooter was Miroslav Kurak, in accordance with Ulemek’s statement. However, in her statement, Branka Prpa, the eyewitness to the crime maintained that Kurak was not the man whom she saw. [p. 118] The Prosecution claimed her testimony was unreliable since she was traumatized by the event, which the Defendants contested. The Court concluded that there was another accomplice and that the killer was an “unknown person”.

The Defendants presented a range of arguments based on the premise that the trial was illegitimate and largely a media ploy to put Serbia in a better position with the European Union. Defendant Radomir Markovic argued that Slavko Curuvija was not the only journalist who was writing against the regime, so there was no reason to single him out to be killed over the all the others. He also stated that it was “illogical to believe” that the government was behind the killing, given the fact that the State had already taken away from Curuvija “all means for work, his newspapers, printing press, so he was no longer functioning, he was not politically active, he did not belong to a single political party, which leads to the conclusion that he could no longer jeopardize anyone”. [p. 13] Markovic claimed that the only reason the trial took place was because the media published articles that Serbia’s ascension to the European Union would be delayed unless the murder of Slavko Curuvija was resolved. [p. 14]

Defendant Milan Radonjic stated that he had ordered secret surveillance of Slavko Curuvija in response to allegations that Curuvija was expected to receive money from “a foreign institution” [p. 28] and that he learned that Curuvija had already been under surveillance since 1998 “together with a greater number of journalists” for his “reporting about [the conflict in] Kosovo.” [p. 37] According to Radonjic, “the only motive for this trial [was] for the public to get an impression of the Secret Service as a criminal organization, which is an utter fabrication.” [p. 34]

Lawyer Zora Dobricanin-Nikodijevic spoke for both Defendants, Milan Radonjic and Ratko Romic, and said that neither the Prosecution nor government bodies “have presented an objective interpretation of the evidence” [p. 44] and that for the last 15 years, “the media has prepared the ground for the claim that the Secret Service is the one responsible for Curuvija’s murder.” [p. 49] Similarly, Miroslav Kurak’s lawyer stated that the Prosecution’s final words “serve only to be published in the media, and nothing else.” [p. 50]

One lawyer for the Defendants also disputed the communications data from the cell towers in the center of Belgrade, one of the most important pieces of evidence, which “placed” the Defendants at the scene of the murder. The lawyer questioned their authenticity by pointing out that it was dubious that the listings were kept for so long during the war, that by law they were not allowed to be kept for more than a year, and that it was illegal for Telekom to keep the data of another operator (Mobtel).

Based on the above evidence, the Court concluded that members of the Serbian State Security Service, Radomir Markovic, Ratko Romic, Milan Radonjic and Miroslav Kurak were guilty of the killing of publisher and journalist Slavko Curuvija.

The Court recognized that Slavko Curuvija , due to his media and public work, had been charged with, as well as convicted of crimes, under the media law of that time. [p. 124] Moreover, media close to the regime portrayed him as a person who was “against the government” [p. 125], and evidence confirmed that the Secret Service labeled him an “enemy of the State” [p. 125]. The Court posited that considering the tensions surrounding the NATO bombing of the country, top government officials could have felt sufficiently threatened to direct Radomir Markovic to liquidate Curuvija. [p. 125] Based on witness testimony, the Court determined that Markovic had directed Milan Radonjic, who was at the time an officer in the Secret Service, to mobilize Ratko Romic, Miroslav Kurak and an Unknown Person to carry out the killing.

After examining the written documentation, the mobile towers data and hearing witnesses, the Court concluded that it was Milan Radonjic who gave the final orders to his subordinates. On the day and approximate time of the murder, he was receiving notifications about Curuvija’s precise location. Similarly, on that date and time, Miroslav Kurak and Ratko Romic had rapid, frequent phone communication, in the vicinity of Slavko Curuvija’s apartment, and that some calls were placed to Radonjic.

Radomir Markovic, who was at the time the Head of the Serbian State Security, was sentenced to 30 years in prison for orchestrating the murder of Slavko Curuvija. The service officer Milan Radonjic was sentenced to 30 years in prison for planning the murder, while secret service agents Ratko Romic and Miroslav Kurak were each sentenced to 20 years in prison for aiding the execution carried out by an Unknown Person.

At the time of the ruling, Radomir Markovic was serving a prison sentence for an unrelated crime, Radonjic and Romic were in home detention while Kurak was in hiding and convicted in absentia.

The Appeals Court in Belgrade (Second Instance)

On July 15, 2020, the Appellate Court revoked the decision of the lower court finding the convictions were based on flawed reasoning and a lack of evidence. The Appellate Court found that the first instance court introduced an Unidentified Person as the direct perpetrator of the crime, although the Prosecutor’s Office for Organized Crime until the end of the proceedings maintained that the fugitive Miroslav Kurak was the one who shot Slavko Ćuruvija. Further, no evidence about an unidentified killer was presented during the trial. The Appellate court reversed and remanded the decision back to the First Instance for reconsideration.

Mixed Outcome

According to the World Press Freedom Index, Serbia currently ranks as number 93 out of 180 countries. The Index found that journalists are frequently subject to attacks, harassment and intimidation, and their appeals at courts are more often ignored than resolved. Over the last 25 years, three journalists have been murdered (Slavko Curuvija is one of them), and there were several attempted murders, none of which have been resolved.

The conviction by the First Instance Court was seen as a landmark ruling as it would mark the first time in the history of Serbia that people responsible for the killing of a journalist would be held accountable. Such an outcome would signify much needed change and would send a clear message that there will be no impunity for crimes against members of the media. According to advocacy groups, such as the Committee to Protect Journalists, it is very important for the Future of Serbia to prosecute all involved in Curuvija’s murder, and they are calling it a “definite step of achieving justice.”

In addition, there is significant evidence that Slavko Curuvija was indeed murdered by members of the State secret police who were acting on powerful orders. So, in a broader context, it can be argued that the State itself is standing trial.

However, not all potentially important witnesses got their day in Court. Franko Frenki Simatović, the founder of the Special Operations Unit of which Milorad Ulemek was a commander and the best man of Miroslav Kurak, accused of killing Curuvija, refused to appear in front of the court, saying that by doing so he would violate the orders of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in the Hague. At the time, Simatović was in between trials in front of the Hague Tribunal.

The decision of the Appellate Court stunned many in Belgrade and in the international community. In its open letter, the Slavko Curuvija Foundation called it an “agony” that “continues for the family, friends and admirers of the murdered journalist, who have already been awaiting justice for more than 21 years,” while the media advocacy organization, Reporters Without Borders, openly asked are judges protecting journalists or their aggressors?

Table of Authorities

National standards, law or jurisprudence

- Serbia, Criminal Code

Articles 4, 33 , 34, 42, 54, 63 - Serbia, Criminal Code Article 114, code 1, point 5

- Serbia, Criminal Code Article 47, code 2 KZ RS

Case Significance

The decision establishes a binding or persuasive precedent within its jurisdiction.

Reports, Analysis, and News Articles:

- Commission Releases Chairman’s Statement on The Assassination of Slavko Curuvija

https://www.csce.gov/international-impact/press-and-media/press-releases/commission-releases-chairmans-statement?sort_by=field_date_value&page=6 - Serbia : four men convicted of Serbian journalist’s murder in 1999

https://rsf.org/en/news/serbia-four-men-convicted-serbian-journalists-murder-1999 - Serbia Convicts State Security Officers of Journalist’s Murder

https://balkaninsight.com/2019/04/05/serbia-convicts-state-security-officers-of-journalists-murder/ - Convictions overturned and retrial ordered for murder of Serbian journalist Ćuruvija

https://ipi.media/convictions-overturned-and-retrial-ordered-for-murder-of-serbian-journalist-curuvija/

O etici i drugim demonima: Dosta više o Kosti K!

O etici i drugim demonima: Dosta više o Kosti K! Tatjana Lazarević, Kossev: Udaraju tamo gde je najslabije, u medije koje i kosovska i srpska vlast targetiraju kao vinovnike zla

Tatjana Lazarević, Kossev: Udaraju tamo gde je najslabije, u medije koje i kosovska i srpska vlast targetiraju kao vinovnike zla Kolega robot na novinarskom zadatku: Šta mu je dozvoljeno, a šta nije. Za sada

Kolega robot na novinarskom zadatku: Šta mu je dozvoljeno, a šta nije. Za sada

Ostavljanje komentara je privremeno obustavljeno iz tehničkih razloga. Hvala na razumevanju.